95 KiB

Potatoes and Portal Guns gaming

CLOSED: [2011-04-26 Tue]

Meh.php programming

CLOSED: [2011-04-27 Wed 00:00]

Transmission, RSS, and XBMC programming python

CLOSED: [2011-04-27 Wed 00:01]

Learning Functional Programming, Part One programming python

CLOSED: [2012-04-09 Mon]

Erlang: The Movie programming erlang

CLOSED: [2013-11-27 Wed]

Getting Organized with Org Mode emacs org_mode git graphviz

CLOSED: [2014-11-25 Tue]

I've been using Emacs Org mode for nearly a year now. For a while I mostly just used it to take and organize notes, but over time I've discovered it's an incredibly useful tool for managing projects and tasks, writing and publishing documents, keeping track of time and todo lists, and maintaining a journal.

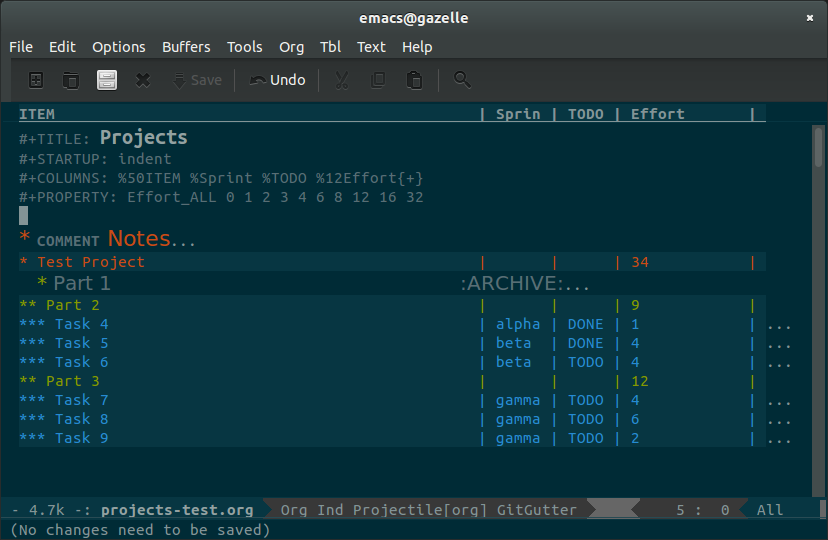

Project Management

Most of what I've been using Org mode for has been breaking down large projects at work into tasks and subtasks. It's really easy to enter projects in as a hierarchy of tasks and task groupings. Using Column View, I was able to dive right into scoping them individually and reporting total estimates for each major segment of work.

Because Org Mode makes building and modifying an outline structure like this so quick and easy, I usually build and modify the project org document while planning it out with my team. Once done, I then manually load that information into our issue tracker and get underway. Occasionally I'll also update tags and progress status in the org document as well as the project progresses, so I can use the same document to plan subsequent development iterations.

Organizing Notes and Code Exercises

More recently, I've been looking into various ways to get more things organized with Org mode. I've been stepping through Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs with some other folks from work, and discovered that Org mode was an ideal fit for keeping my notes and exercise work together. The latter is neatly managed by Babel, which let me embed and edit source examples and my excercise solutions right in the org document itself, and even export them to one or more scheme files to load into my interpreter.

Exporting and Publishing Documents

Publishing my notes with org is also a breeze. I've published project plans and proposals to PDF to share with colleagues, and exported my SICP notes to html and dropped them into a site built with Jekyll. Embedding graphs and diagrams into exported documents using Graphviz, Mscgen, and PlantUML has also really helped with putting together some great project plans and documentation. A lot of great examples using those tools (and more!) can be found here.

Emacs Configuration

While learning all the cool things I could do with Org mode and Babel, it was only natural I'd end up using it to reorganize my Emacs configuration. Up until that point, I'd been managing my configuration in a single init.el file, plus a directory full of mode or purpose-specific elisp files that I'd loop through and load. Inspired primarily by the blog post, "Making Emacs Work For Me", and later by others such as Sacha Chua's Emacs configuration, I got all my configs neatly organized into a single org file that gets loaded on startup. I've found it makes it far easier to keep track of what I've got configured, and gives me a reason to document and organize things neatly now that it's living a double life as a published document on GitHub. I've still got a directory lying around with autoloaded scripts, but now it's simply reserved for tinkering and sensitive configuration.

Tracking Habits

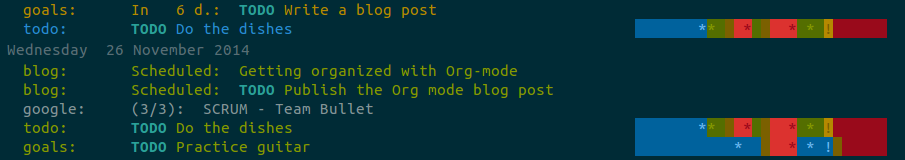

Another great feature of Org mode that I've been taking advantage of a lot more lately is the Agenda. By defining some org files as being agenda files, Org mode can examine these files for TODO entries, scheduled tasks, deadlines and more to build out useful agenda views to get a quick handle on what needs to be done and when. While at first I started by simply syncing down my google calendars as org-files (using ical2org.awk), I've started managing TODO lists in a dedicated org file. By adding tasks to this file, scheduling them, and setting deadlines, I've been doing a much better job of keeping track of things I need to get done and (even more importantly) when I need to get them done.

This works not only for one-shot tasks, but also habits and other repetitive tasks. It's possible to schedule a task that should be done every day, every few days, or maybe every first sunday of a month. For example, I've set up repeating tasks to write a blog post at least once a month, practice guitar every two to three days, and to do the dishes every one or two days. The agenda view can even show a small, colorized graph next to each repeating task that paints a picture of how well (or not!) I've been getting those tasks done on time.

Keeping a Journal and Tracking Work

The last thing I've been using (which I'm still getting a handle on) is using Capture to take and store notes, keep a journal, and even track time on tasks at work.

(setq org-capture-templates

'(("j" "Journal Entry" plain

(file+datetree "~/org/journal.org")

"%U\n\n%?" :empty-lines-before 1)

("w" "Log Work Task" entry

(file+datetree "~/org/worklog.org")

"* TODO %^{Description} %^g\n%?\n\nAdded: %U"

:clock-in t

:clock-keep t)))

(global-set-key (kbd "C-c c") 'org-capture)

(setq org-clock-persist 'history)

(org-clock-persistence-insinuate)For my journal, I've configured a capture template that I can use to write down a new entry that will be stored with a time stamp appended into its own org file, organized under headlines by year, month and date.

For work tasks, I have another capture template configured that will log and tag a task into another org file, also organized by date, which will automatically start tracking time for that task. Once done, I can simply clock out and check the time I've spent, and can easily find it later to clock in again, add notes, or update its status. This helps me keep track of what I've gotten done during the day, keep notes on what I was doing at any point in time, and get a better idea of how long it takes me to do different types of tasks.

Conclusion

There's a lot that can be done with Org mode, and I've only just scratched the surface. The simple outline format provided by Org mode lends itself to doing all sorts of things, be it organizing notes, keeping a private or work journal, or writing a book or technical document. I've even written this blog post in Org mode! There's tons of functionality that can be built on top of it, yet the underlying format itself remains simple and easy to work with. I've never been great at keeping myself organized, but Org mode is such a delight to use that I can't help trying anyway. If it can work for me, maybe it can work for you, too!

There's tons of resources for finding new ways for using Org mode, and I'm still discovering cool things I can track and integrate with it. I definitely recommend reading through Sacha Chua's Blog, as well as posts from John Wiegley. I'm always looking for more stuff to try out. Feel free to drop me a line if you find or are using something you think is cool or useful!

Adventuring Through SICP programming lisp

CLOSED: [2015-01-01 Thu]

Back in May, a coworker and I got the idea to start up a little seminar after work every couple of weeks with the plan to set aside some time to learn and discuss new ideas together, along with anyone else who cared to join us.

Learning Together

Over the past several months, we've read our way through the first three chapters of the book, watched the related video lectures, and did (most of) the exercises.

Aside from being a great excuse to unwind with friends after work (which it is!), it's proved to be a great way to get through the material. Doing a section of a chapter every couple of weeks is an easy goal to meet, and meeting up to discuss it becomes something to look forward to. We all get to enjoy a sense of accomplishment in learning stuff that can be daunting or difficult to set aside time for alone.

The best part, by far, is getting different perspectives on the material. Most of my learning tends to be solitary, so it's refreshing to do it with a group. By reviewing the different concepts together, we're able to gain insights and clarity we'd never manage on our own. Even the simplest topics can spur interesting conversations.

SICP

Our first adventure together so far has been the venerable Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs. This book had been on my todo list for a long time, but never quite bubbled to the top. I'm glad to have the opportunity to go through it in this format, since there's plenty of time to let really get into the excercises and let the lessons sink in.

SICP was originally an introductory textbook for MIT computer programming courses. What sets it apart from most, though, is that it doesn't focus so much on learning a particular programming language (while the book does use and cover MIT Scheme) as it does on identifying and abstracting out patterns common to most programming problems. Because of that, the book is every bit as useful and illuminating as ever, especially now that functional paradigms are re-entering the spotlight and means of abstracting and composing systems are as important as ever.

What's next?

We've still got plenty of SICP left to get through. We've only just gotten through Chapter 4, section 1, which has us building a scheme interpreter in scheme, so there's plenty of fun left to be had there.

We're also staring to do some smaller, lunchtime review meetings following the evening discussions to catch up the folks that can't make it. I may also try sneaking in some smaller material, like interesting blog posts, to keep things lively.

If anyone's interested, I have the exercise work along with some notes taken during the meetings hosted online. I apologize for the lack of notes early on, I've been trying to get better at capturing memorable excerpts and conversation topics recently. I may have to put some more posts together later on summarizing what we discussed for each chapter; if and when I do, they'll be posted on the seminar website.

Coders at Work programming books

CLOSED: [2015-01-28 Wed]

A few days before leaving work for a week and a half of flying and cruising to escape frigid Pennsylvania, I came across a Joe Armstrong quote during my regularly scheduled slacking off on twitter and Hacker News. I'd come across a couple times before, only this time I noticed it had a source link. This led me to discovering (and shortly thereafter, buying) Peter Seibel's "Coders at Work – Reflections on the Craft of Programming". I loaded it onto my nook, and off I went.

The book is essentially a collection of interviews with a series of highly accomplished software developers. Each of them has their own fascinating insights into the craft and its rich history.

While making my way through the book, I highlighted some excerpts that, for one reason or another, resonated with me. I've organized and elaborated on them below.

Incremental Changes

CLOSED: [2015-01-20 Tue 20:59] <<fitzpatrick-increments>>

I've seen young programmers say, "Oh, shit, it doesn't work," and then rewrite it all. Stop. Try to figure out what's going on. Learn how to write things incrementally so that at each stage you could verify it.

– Brad Fitzpatrick

I can remember doing this to myself when I was still relatively new to coding (and even worse, before I discovered source control!). Some subroutine or other would be misbehaving, and rather than picking it apart and figuring out what it was I'd done wrong, I'd just blow it away and attempt to write it fresh. While I might be successful, that likely depended on the issue being some sort of typo or missed logic; if it was broken because I misunderstood something or had a bad plan to begin with, rewriting it would only result in more broken code, sometimes in more or different ways than before. I don't think I've ever rewritten someone else's code without first at least getting a firm understanding of it and what it was trying to accomplish, but even then, breaking down changes piece by piece makes it all the easier to maintain sanity.

I do still sometimes catch myself doing too much at once when building a new feature or fixing a bug. I may have to fix a separate bug that's in my way, or I may have to make several different changes in various parts of the code. If I'm not careful, things can get out of hand pretty quickly, and before I know it I have a blob of changes strewn across the codebase in my working directory without a clear picture of what's what. If something goes wrong, it can be pretty tough to sort out which change broke things (or fixed them). Committing changes often helps tremendously to avoid this sort of situation, and when I catch myself going off the rails I try to find a stopping point and split changes up into commits as soon as possible to regain control. Related changes and fixes can always be squashed together afterwards to keep things tidy.

Specifications & Documentation

CLOSED: [2015-01-20 Tue 20:59] <<bloch-customers>>

Many customers won't tell you a problem; they'll tell you a solution. A customer might say, for instance, "I need you to add support for the following 17 attributes to this system. Then you have to ask, 'Why? What are you going to do with the system? How do you expect it to evolve?'" And so on. You go back and forth until you figure out what all the customer really needs the software to do. These are the use cases.

– Joshua Bloch

Whether your customer is your customer, or your CEO, the point stands: customers are really bad at expressing what they want. It's hard to blame them, though; analyzing what you really want and distilling it into a clear specification is tough work. If your customer is your boss, it can be intimidating to push back with questions like "Why?", but if you can get those questions answered you'll end up with a better product, a better understanding of the product, and a happy customer. The agile process of doing quick iterations to get tangible results in front of them is a great way of getting the feedback and answers you need.

<<armstrong-documentation>>

The code shows me what it does. It doesn't show me what it's supposed to do. I think the code is the answer to a problem. If you don't have the spec or you don't have any documentation, you have to guess what the problem is from the answer. You might guess wrong.

– Joe Armstrong

Once you've got the definition of what you've got to build and how it's got to work, it's extremely important that you get it documented. Too often, I'm faced with code that's doing something in some way that somebody, either a customer or a developer reading it, takes issue with, and there's no documentation anywhere on why it's doing what it's doing. What happens next is anybody's guess. Code that's clear and conveys its intent is a good start towards avoiding this sort of situation. Comments explaining intent help too, though making sure they're kept up to date with the code can be challenging. At the very least, I try to promote useful commit messages explaining what the purpose of a change is, and reference a ticket in our issue tracker which (hopefully) has a clear accounting of the feature or bugfix that prompted it.

Pair Programming

CLOSED: [2015-01-20 Tue 21:03] <<armstrong-pairing>>

… if you don't know what you're doing then I think it can be very helpful with someone who also doesn't know what they're doing. If you have one programmer who's better than the other one, then there's probably benefit for the weaker programmer or the less-experienced programmer to observe the other one. They're going to learn something from that. But if the gap's too great then they won't learn, they'll just sit there feeling stupid.

– Joe Armstrong

Pairing isn't something I do much. At least, it's pretty rare that I have someone sitting next to me as I code. I do involve peers while I'm figuring out what I want to build as often as I can. The tougher the problem, the more important it is, I think, to get as much feedback and brainstorming in as possible. This way, everybody gets to tackle the problem and learn together, and anyone's input, however small it might seem, can be the key to the "a-ha" moment to figuring out a solution.

Peer Review

CLOSED: [2015-01-25 Sun 22:44] <<crockford-reading>>

I think an hour of code reading is worth two weeks of QA. It's just a really effective way of removing errors. If you have someone who is strong reading, then the novices around them are going to learn a lot that they wouldn't be learning otherwise, and if you have a novice reading, he's going to get a lot of really good advice.

– Douglas Crockford

Just as important as designing the software as a team, I think, is reviewing it as a team. In doing so, each member of the team has an opportunity to understand how the system has been implemented, and to offer their suggestions and constructive criticisms. This helps the team grow together, and results in a higher quality of code overall. This benefits QA as well as the developers themselves for the next time they find themselves in that particular bit of the system.

Object-Oriented Programming

CLOSED: [2015-01-20 Tue 20:59] <<armstrong-oop>>

I think the lack of reusability comes in object-oriented languages, not in functional languages. Because the problem with object-oriented languages is they've got all this implicit environment that they carry around with them. You wanted a banana but what you got was a gorilla holding the banana and the entire jungle.

– Joe Armstrong

A lot has been written on why OOP isn't the great thing it claims to be, or was ever intended to be. Having grappled with it myself for years, attempting to find ways to keep my code clean, concise and extensible, I've more or less come to the same conclusion as Armstrong in that coupling data structures with behaviour makes for a terrible mess. Dividing the two led to a sort of moment of clarity; there was no more confusion about what methods belong on what object. There was simply the data, and the methods that act on it. I am still struggling a bit, though, on how to bring this mindset to the PHP I maintain at work. The language seems particularly ill-suited to managing complex data structures (or even simple ones – vectors and hashes are bizarrely intertwined).

Writing

CLOSED: [2015-01-28 Wed 22:42] <<bloch-writing>>

You should read [Elements of Style] for two reasons: The first is that a large part of every software engineer's job is writing prose. If you can't write precise, coherent, readable specs, nobody is going to be able to use your stuff. So anything that improves your prose style is good. The second reason is that most of the ideas in that book are also applicable to programs.

– Joshua Bloch

<<crockford-writing>>

My advice to everybody is pretty much the same, to read and write.

…

Are you a good Java programmer, a good C programmer, or whatever? I don't care. I just want to know that you know how to put an algorithm together, you understand data structures, and you know how to document it.

– Douglas Crockford

<<knuth-writing>>

This is what literate programming is so great for –

I can talk to myself. I can read my program a year later and know exactly what I was thinking.

– Donald Knuth

The more I've program professionally, the clearer it is that writing (and communication in general) is a very important skill to develop. Whether it be writing documentation, putting together a project plan, or whiteboarding and discussing something, clear and concise communication skills are a must. Clarity in writing translates into clarity in coding as well, in my opinion. Code that is short, to the point, clear in its intention, making good use of structure and wording (in the form of function and variable names) is far easier to read and reason about than code that is disorganized and obtuse.

Knuth

CLOSED: [2015-01-28 Wed 22:42] <<crockford-knuth>>

I tried to make familiarity with Knuth a hiring criteria, and I was disappointed that I couldn't find enough people that had read him. In my view, anybody who calls himself a professional programmer should have read Knuth's books or at least should have copies of his books.

– Douglas Crockford

<<steele-knuth>>

… Knuth is really good at telling a story about code. When you read your way through The Art of Computer Programming and you read your way through an algorithm, he's explained it to you and showed you some applications and given you some exercises to work, and you feel like you've been led on a worthwhile journey.

– Guy Steele

<<norvig-knuth>>

At one point I had [The Art of Computer Programming] as my monitor stand because it was one of the biggest set of books I had, and it was just the right height. That was nice because it was always there, and I guess then I was more prone to use it as a reference because it was right in front of me.

– Peter Norvig

I haven't read any of Knuth's books yet, which is something I'll have to rectify soon. I don't think I have the mathematical background necessary to get through some of his stuff, but I expect it will be rewarding nonetheless. I'm also intrigued by his concept of literate programming, and I'm curious to learn more about TeX. I imagine I'll be skimming through TeX: The Program pretty soon now that I've finished Coders at Work :)

Birthday Puzzle programming prolog

CLOSED: [2015-04-18 Sat]

This logic puzzle has been floating around the internet lately. When I caught wind of it, I thought it would be a great exercise to tackle using Prolog. I'm not especially good with the language yet, so it added to the challenge a bit, but it was a pretty worthwhile undertaking. When I got stumped, I discovered that mapping out the birthdays into a grid helped me visualize the problem and ultimately solve it, so I've included that with my prolog code so you can see how I arrived at the answer.

The Puzzle

Albert and Bernard have just met Cheryl. “When is your birthday?” Albert asked Cheryl. Cheryl thought for a moment and said, “I won’t tell you, but I’ll give you some clues”. She wrote down a list of ten dates:

- May 15, May 16, May 19

- June 17, June 18

- July 14, July 16

- August 14, August 15, August 17

“One of these is my birthday,” she said.

Cheryl whispered in Albert’s ear the month, and only the month, of her birthday. To Bernard, she whispered the day, and only the day. “Can you figure it out now?” she asked Albert.

Albert: “I don’t know when your birthday is, but I know Bernard doesn’t know, either.”

Bernard: “I didn’t know originally, but now I do.”

Albert: “Well, now I know, too!”

When is Cheryl’s birthday?

The Solution

The Dates

To start off, i entered each of the possible birthdays as facts:

possible_birthday(may, 15).

possible_birthday(may, 16).

possible_birthday(may, 19).

possible_birthday(june, 17).

possible_birthday(june, 18).

possible_birthday(july, 14).

possible_birthday(july, 16).

possible_birthday(august, 14).

possible_birthday(august, 15).

possible_birthday(august, 17).And here they are, mapped out in a grid:

| May | June | July | August | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | X | X | ||

| 15 | X | X | ||

| 16 | X | X | ||

| 17 | X | X | ||

| 18 | X | |||

| 19 | X |

Albert's Statement

I don’t know when your birthday is,…

Albert only knows the month, and the month isn't enough to uniquely identify Cheryl's birthday.

month_is_not_unique(M) :-

bagof(D, possible_birthday(M, D), Days),

length(Days, Len),

Len > 1.… but I know Bernard doesn’t know, either.

Albert knows that Bernard doesn't know Cheryl's birthday. Therefore, the day alone isn't enough to know Cheryl's birthday, and we can infer that the month of Cheryl's birthday does not include any of the unique dates.

day_is_not_unique(D) :-

bagof(M, possible_birthday(M, D), Months),

length(Months, Len),

Len > 1.

month_has_no_unique_days(M) :-

forall(possible_birthday(M,D),

day_is_not_unique(D)).Based on what Albert knows at this point, let's see how we've reduced the possible dates:

part_one(M,D) :-

possible_birthday(M,D),

month_is_not_unique(M),

month_has_no_unique_days(M),

day_is_not_unique(D).Results = [ (july, 14), (july, 16), (august, 14), (august, 15), (august, 17)].

So the unique days (the 18th and 19th) are out, as are the months that contained them (May and June).

| July | August | |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | X | X |

| 15 | X | |

| 16 | X | |

| 17 | X |

Bernard's Statement

I didn’t know originally, but now I do.

For Bernard to know Cheryl's birthday, the day he knows must be unique within the constraints we have so far.

day_is_unique(Month, Day) :-

findall(M, part_one(M, Day), [Month]).

part_two(Month, Day) :-

possible_birthday(Month, Day),

day_is_unique(Month, Day).Results = [ (july, 16), (august, 15), (august, 17)].

Both July and August contain the 14th, so that row is out.

| July | August | |

|---|---|---|

| 15 | X | |

| 16 | X | |

| 17 | X |

Albert's Second Statement

Well, now I know, too!

Albert's month must be the remaining unique month:

month_is_not_unique(Month, Day) :-

findall(D, part_two(Month, D), [Day]).

part_three(Month, Day) :-

possible_birthday(Month, Day),

month_is_not_unique(Month, Day).Results = [ (july, 16)].

August had two possible days, so it's now clear that the only possible unique answer is July 16th.

| July | |

|---|---|

| 15 | |

| 16 | X |

| 17 |

Cheryl's Birthday

cheryls_birthday(Month, Day) :-

part_three(Month, Day).Month = july, Day = 16.

So, there we have it. Cheryl's birthday is July 16th!

| July | |

|---|---|

| 16 | X |

Keeping Files And Configuration In Sync git

CLOSED: [2015-04-20 Mon]

I have a few computers I use on a daily basis, and I like to keep the same emacs and shell configuration on all of them, along with my org files and a handful of scripts. Since I'm sure other people have this problem as well, I'll share what I'm doing so anyone can learn from (or criticise) my solutions.

Git for configuration and projects

I'm a software developer, so keeping things in git just makes sense to me. I keep my org files in a privately hosted git repository, and Emacs and Zsh configurations in a public repo on github. My blog is also hosted and published on github as well; I like having it cloned to all my machines so I can work on drafts wherever I may be.

My .zshrc installs oh-my-zsh if it isn't installed already, and sets up my shell theme, path, and some other environmental things.

My Emacs configuration behaves similarly, making use of John Wiegley's excellent use-package tool to ensure all my packages are installed if they're not already there and configured the way I like them.

All I have to do to get running on a new system is to install git, emacs and zsh, clone my repo, symlink the files, and grab a cup of tea while everything installs.

Bittorrent sync for personal settings & books

For personal configuration that doesn't belong in and/or is too sensitive to be in a public repo, I have a folder of dotfiles and things that I sync between my machines using Bittorrent Sync. The dotfiles are arranged into directories by their purpose:

[correlr@reason:~/dotenv]

% tree -a -L 2

.

├── authinfo

│ └── .authinfo.gpg

├── bin

│ └── .bin

├── emacs

│ ├── .bbdb

│ └── .emacs.local.d

├── mail

│ ├── .gnus.el

│ ├── .signature

├── README.org

├── .sync

│ ├── Archive

│ ├── ID

│ ├── IgnoreList

│ └── StreamsList

├── tex

│ └── texmf

├── xmonad

│ └── .xmonad

└── zsh

└── .zshenv

This folder structure allows my configs to be easily installed using

GNU Stow from my dotenv folder:

stow -vvS *

Running that command will, for each file in each of the directories, create a symlink to it in my home folder if there isn't a file or directory with that name there already.

Bittorrent sync also comes in handy for syncing my growing Calibre ebook collection, which outgrew my Dropbox account a while back.

Drawing Git Graphs with Graphviz and Org-Mode emacs org_mode git graphviz

CLOSED: [2015-07-12 Sun]

Digging through Derek Feichtinger's org-babel examples (which I came across via irreal.org), I found he had some great examples of displaying git-style graphs using graphviz. I thought it'd be a fun exercise to generate my own graphs based on his graphviz source using elisp, and point it at actual git repos.

Getting Started

I started out with the goal of building a simple graph showing a mainline branch and a topic branch forked from it and eventually merged back in.

Using Derek's example as a template, I described 5 commits on a master branch, plus two on a topic branch.

digraph G {

rankdir="LR";

bgcolor="transparent";

node[width=0.15, height=0.15, shape=point, color=white];

edge[weight=2, arrowhead=none, color=white];

node[group=master];

1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 4 -> 5;

node[group=branch];

2 -> 6 -> 7 -> 4;

}The resulting image looks like this:

Designing the Data Structure

The first thing I needed to do was describe my data structure. Leaning on my experiences reading and working through SICP, I got to work building a constructor function, and several accessors.

I decided to represent each node on a graph with an id, a list of parent ids, and a group which will correspond to the branch on the graph the commit belongs to.

(defun git-graph/make-node (id &optional parents group)

(list id parents group))

(defun git-graph/node-id (node)

(nth 0 node))

(defun git-graph/node-parents (node)

(nth 1 node))

(defun git-graph/node-group (node)

(nth 2 node))Converting the structure to Graphviz

Now that I had my data structures sorted out, it was time to step through them and generate the graphviz source that'd give me the nice-looking graphs I was after.

The graph is constructed using the example above as a template. The nodes are defined first, followed by the edges between them.

(defun git-graph/to-graphviz (id nodes)

(string-join

(list

(concat "digraph " id " {")

"bgcolor=\"transparent\";"

"rankdir=\"LR\";"

"node[width=0.15,height=0.15,shape=point,fontsize=8.0,color=white,fontcolor=white];"

"edge[weight=2,arrowhead=none,color=white];"

(string-join

(-map #'git-graph/to-graphviz-node nodes)

"\n")

(string-join

(-uniq (-flatten (-map

(lambda (node) (git-graph/to-graphviz-edges node nodes))

nodes)))

"\n")

"}")

"\n"))For the sake of readability, I'll format the output:

(defun git-graph/to-graphviz-pretty (id nodes)

(with-temp-buffer

(graphviz-dot-mode)

(insert (git-graph/to-graphviz id nodes))

(indent-region (point-min) (point-max))

(buffer-string)))Each node is built, setting its group attribute when applicable.

(defun git-graph/to-graphviz-node (node)

(let ((node-id (git-graph/to-graphviz-node-id

(git-graph/node-id node))))

(concat node-id

(--if-let (git-graph/node-group node)

(concat "[group=\"" it "\"]"))

";")))Graphviz node identifiers are quoted to avoid running into issues with spaces or other special characters.

(defun git-graph/to-graphviz-node-id (id)

(format "\"%s\"" id))For each node, an edge is built connecting the node to each of its parents.

(defun git-graph/to-graphviz-edges (node &optional nodelist)

(let ((node-id (git-graph/node-id node))

(parents (git-graph/node-parents node))

(node-ids (-map #'git-graph/node-id nodelist)))

(-map (lambda (parent)

(unless (and nodelist (not (member parent node-ids)))

(git-graph/to-graphviz-edge node-id parent)))

parents)))

(defun git-graph/to-graphviz-edge (from to)

(concat

(git-graph/to-graphviz-node-id to)

" -> "

(git-graph/to-graphviz-node-id from)

";"))With that done, the simple graph above could be generated with the following code:

(git-graph/to-graphviz-pretty

"example"

(list (git-graph/make-node 1 nil "master")

(git-graph/make-node 2 '(1) "master")

(git-graph/make-node 3 '(2) "master")

(git-graph/make-node 4 '(3 7) "master")

(git-graph/make-node 5 '(4) "master")

(git-graph/make-node 6 '(2) "branch")

(git-graph/make-node 7 '(6) "branch")))Which generates the following graphviz source:

<<git-example()>>The generated image matches the example exactly:

Adding Labels

The next thing my graph needed was a way of labeling nodes. Rather than trying to figure out some way of attaching a separate label to a node, I decided to simply draw a labeled node as a box with text.

digraph G {

rankdir="LR";

bgcolor="transparent";

node[width=0.15, height=0.15, shape=point,fontsize=8.0,color=white,fontcolor=white];

edge[weight=2, arrowhead=none,color=white];

node[group=main];

1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 4 -> 5;

5[shape=box,label=master];

node[group=branch1];

2 -> 6 -> 7 -> 4;

7[shape=box,label=branch];

}Updating the Data Structure

I updated my data structure to support an optional label applied to a node. I opted to store it in an associative list alongside the group.

(defun git-graph/make-node (id &optional parents options)

(list id parents options))

(defun git-graph/node-id (node)

(nth 0 node))

(defun git-graph/node-parents (node)

(nth 1 node))

(defun git-graph/node-group (node)

(cdr (assoc 'group (nth 2 node))))

(defun git-graph/node-label (node)

(cdr (assoc 'label (nth 2 node))))Updating the Graphviz node generation

The next step was updating the Graphviz generation functions to handle the new data structure, and set the shape and label attributes of labeled nodes.

(defun git-graph/to-graphviz-node (node)

(let ((node-id (git-graph/to-graphviz-node-id (git-graph/node-id node))))

(concat node-id

(git-graph/to-graphviz-node--attributes node)

";")))

(defun git-graph/to-graphviz-node--attributes (node)

(let ((attributes (git-graph/to-graphviz-node--compute-attributes node)))

(and attributes

(concat "["

(mapconcat (lambda (pair)

(format "%s=\"%s\""

(car pair) (cdr pair)))

attributes

", ")

"]"))))

(defun git-graph/to-graphviz-node--compute-attributes (node)

(-filter #'identity

(append (and (git-graph/node-group node)

(list (cons 'group (git-graph/node-group node))))

(and (git-graph/node-label node)

(list (cons 'shape 'box)

(cons 'label (git-graph/node-label node)))))))I could then label the tips of each branch:

(git-graph/to-graphviz-pretty

"labeled"

(list (git-graph/make-node 1 nil '((group . "master")))

(git-graph/make-node 2 '(1) '((group . "master")))

(git-graph/make-node 3 '(2) '((group . "master")))

(git-graph/make-node 4 '(3 7) '((group . "master")))

(git-graph/make-node 5 '(4) '((group . "master")

(label . "master")))

(git-graph/make-node 6 '(2) '((group . "branch")))

(git-graph/make-node 7 '(6) '((group . "branch")

(label . "branch")))))Automatic Grouping Using Leaf Nodes

Manually assigning groups to each node is tedious, and easy to accidentally get wrong. Also, with the goal to graph git repositories, I was going to have to figure out groupings automatically anyway.

To do this, it made sense to traverse the nodes in topological order.

Repeating the example above,

digraph G {

rankdir="LR";

bgcolor="transparent";

node[width=0.15, height=0.15, shape=circle, color=white, fontcolor=white];

edge[weight=2, arrowhead=none, color=white];

node[group=main];

1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 4 -> 5;

node[group=branch1];

2 -> 6 -> 7 -> 4;

}

These nodes can be represented (right to left) in topological order as

either 5, 4, 3, 7, 6, 2, 1 or 5, 4, 7, 6, 3, 2, 1.

Having no further children, 5 is a leaf node, and can be used as a

group. All first parents of 5 can therefore be considered to be in

group 5.

7 is a second parent to 4, and so should be used as the group for

all of its parents not present in group 5.

(defun git-graph/group-topo (nodelist)

(reverse

(car

(-reduce-from

(lambda (acc node)

(let* ((grouped-nodes (car acc))

(group-stack (cdr acc))

(node-id (git-graph/node-id node))

(group-from-stack (--if-let (assoc node-id group-stack)

(cdr it)))

(group (or group-from-stack node-id))

(parents (git-graph/node-parents node))

(first-parent (first parents)))

(if group-from-stack

(pop group-stack))

(if (and first-parent (not (assoc first-parent group-stack)))

(push (cons first-parent group) group-stack))

(cons (cons (git-graph/make-node node-id

parents

`((group . ,group)

(label . ,(git-graph/node-label node))))

grouped-nodes)

group-stack)))

nil

nodelist))))While iterating through the node list, I maintained a stack of pairs built from the first parent of the current node, and the current group. To determine the group, the head of the stack is checked to see if it contains a group for the current node id. If it does, that group is used and it is popped off the stack, otherwise the current node id is used.

The following table illustrates how the stack is used to store and assign group relationships as the process iterates through the node list:

| Node | Parents | Group Stack | Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | (4) | (4 . 5) | 5 |

| 4 | (3 7) | (3 . 5) | 5 |

| 3 | (2) | (2 . 5) | 5 |

| 7 | (6) | (6 . 7) (2 . 5) | 7 |

| 6 | (2) | (2 . 5) | 7 |

| 2 | (1) | (1 . 5) | 5 |

| 1 | 5 |

Graph without automatic grouping

(git-graph/to-graphviz-pretty

"nogroups"

(list (git-graph/make-node 5 '(4) '((label . master)))

(git-graph/make-node 4 '(3 7))

(git-graph/make-node 3 '(2))

(git-graph/make-node 7 '(6) '((label . develop)))

(git-graph/make-node 6 '(2))

(git-graph/make-node 2 '(1))

(git-graph/make-node 1 nil)))Graph with automatic grouping

(git-graph/to-graphviz-pretty

"autogroups"

(git-graph/group-topo

(list (git-graph/make-node 5 '(4) '((label . master)))

(git-graph/make-node 4 '(3 7))

(git-graph/make-node 3 '(2))

(git-graph/make-node 7 '(6) '((label . develop)))

(git-graph/make-node 6 '(2))

(git-graph/make-node 2 '(1))

(git-graph/make-node 1 nil))))Graphing a Git Repository

Satisfied that I had all the necessary tools to start graphing real git repositories, I created an example repository to test against.

Creating a Sample Repository

Using the following script, I created a sample repository to test against. I performed the following actions:

- Forked a develop branch from master.

- Forked a feature branch from develop, with two commits.

- Added another commit to develop.

- Forked a second feature branch from develop, with two commits.

- Merged the second feature branch to develop.

- Merged develop to master and tagged it.

mkdir /tmp/test.git

cd /tmp/test.git

git init

touch README

git add README

git commit -m 'initial'

git commit --allow-empty -m 'first'

git checkout -b develop

git commit --allow-empty -m 'second'

git checkout -b feature-1

git commit --allow-empty -m 'feature 1'

git commit --allow-empty -m 'feature 1 again'

git checkout develop

git commit --allow-empty -m 'third'

git checkout -b feature-2

git commit --allow-empty -m 'feature 2'

git commit --allow-empty -m 'feature 2 again'

git checkout develop

git merge --no-ff feature-2

git checkout master

git merge --no-ff develop

git tag -a 1.0 -m '1.0!'Generating a Graph From a Git Branch

The first order of business was to have a way to call out to git and return the results:

(defun git-graph/git-execute (repo-url command &rest args)

(with-temp-buffer

(shell-command (format "git -C \"%s\" %s"

repo-url

(string-join (cons command args)

" "))

t)

(buffer-string)))

Next, I needed to get the list of commits for a branch in topological

order, with a list of parent commits for each. It turns out git

provides exactly that via its rev-list command.

(defun git-graph/git-rev-list (repo-url head)

(-map (lambda (line) (split-string line))

(split-string (git-graph/git-execute

repo-url

"rev-list" "--topo-order" "--parents" head)

"\n" t)))I also wanted to label branch heads wherever possible. To do this, I looked up the revision name from git, discarding it if it was relative to some other named commit.

(defun git-graph/git-label (repo-url rev)

(let ((name (string-trim

(git-graph/git-execute repo-url

"name-rev" "--name-only" rev))))

(unless (s-contains? "~" name)

name)))Generating the graph for a single branch was as simple as iterating over each commit and creating a node for it.

(defun git-graph/git-graphs-head (repo-url head)

(git-graph/group-topo

(-map (lambda (rev-with-parents)

(let* ((rev (car rev-with-parents))

(parents (cdr rev-with-parents))

(label (git-graph/git-label repo-url rev)))

(git-graph/make-node rev parents

`((label . ,label)))))

(git-graph/git-rev-list repo-url head))))

Here's the result of graphing the master branch:

(git-graph/to-graphviz-pretty

"git"

(git-graph/git-graphs-head

"/tmp/test.git"

"master")) <<graph-git-branch()>>Graphing Multiple Branches

To graph multiple branches, I needed a function for combining histories. To do so, I simply append any nodes I don't already know about in the first history from the second.

(defun git-graph/+ (a b)

(append a

(-remove (lambda (node)

(assoc (git-graph/node-id node) a))

b)))From there, all that remained was to accumulate the branch histories and output the complete graph:

(defun git-graph/git-load (repo-url heads)

(-reduce #'git-graph/+

(-map (lambda (head)

(git-graph/git-graphs-head repo-url head))

heads)))And here's the example repository, graphed in full:

(git-graph/to-graphviz-pretty

"git"

(git-graph/git-load

"/tmp/test.git"

'("master" "feature-1"))) <<graph-git-repo()>>Things I may add in the future

Limiting Commits to Graph

Running this against repos with any substantial history can make the graph unwieldy. It'd be a good idea to abstract out the commit list fetching, and modify it to support different ways of limiting the history to display.

Ideas would include:

- Specifying commit ranges

- Stopping at a common ancestor to all graphed branches (e.g., using

git-merge-base). - Other git commit limiting options, like searches, showing only merge or non-merge commits, etc.

Collapsing History

Another means of reducing the size of the resulting graph would be to collapse unimportant sections of it. It should be possible to collapse a section of the graph, showing a count of skipped nodes.

The difficult part would be determining what parts aren't worth drawing. Something like this would be handy, though, for concisely graphing the state of multiple ongoing development branches (say, to get a picture of what's been going on since the last release, and what's still incomplete).

digraph G {

rankdir="LR";

bgcolor="transparent";

node[width=0.15,height=0.15,shape=point,color=white];

edge[weight=2,arrowhead=none,color=white];

node[group=main];

1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 4 -> 5;

node[group=branch];

2 -> 6 -> 7 -> 8 -> 9 -> 10 -> 4;

} digraph G {

rankdir="LR";

bgcolor="transparent";

node[width=0.15,height=0.15,shape=point,color=white];

edge[weight=2,arrowhead=none,color=white,fontcolor=white];

node[group=main];

1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 4 -> 5;

node[group=branch];

2 -> 6;

6 -> 10[style=dashed,label="+3"];

10 -> 4;

}Clean up and optimize the code a bit

Some parts of this (particularly, the grouping) are probably pretty inefficient. If this turns out to actually be useful, I may take another crack at it.

Final Code

In case anyone would like to use this code for anything, or maybe just pick it apart and play around with it, all the Emacs Lisp code in this post is collected into a single file below:

;;; git-graph.el --- Generate git-style graphs using graphviz

;; Copyright (c) 2015 Correl Roush <correl@gmail.com>

;;; License:

;; This program is free software; you can redistribute it and/or modify

;; it under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by

;; the Free Software Foundation; either version 3, or (at your option)

;; any later version.

;;

;; This program is distributed in the hope that it will be useful,

;; but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of

;; MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. See the

;; GNU General Public License for more details.

;;

;; You should have received a copy of the GNU General Public License

;; along with GNU Emacs; see the file COPYING. If not, write to the

;; Free Software Foundation, Inc., 51 Franklin Street, Fifth Floor,

;; Boston, MA 02110-1301, USA.

;;; Commentary:

;;; Code:

(require 'dash)

<<git-graph/structure>>

<<git-graph/adder>>

<<git-graph/to-graphviz>>

<<git-graph/to-graphviz-nodes>>

<<git-graph/to-graphviz-edges>>

<<git-graph/group-topo>>

<<git-graph/from-git>>

(provide 'git-graph)

;;; git-graph.el ends hereDownload: git-graph.el

Use a different theme when publishing Org files emacs org_mode

CLOSED: [2016-02-23 Tue]

I've been using material-theme lately, and I sometimes switch around, but I've found that solarized produces the best exported code block results. To avoid having to remember to switch themes when exporting, I wrote a quick wrapper for org-export to do it for me:

(defun my/with-theme (theme fn &rest args)

(let ((current-themes custom-enabled-themes))

(mapcar #'disable-theme custom-enabled-themes)

(load-theme theme t)

(let ((result (apply fn args)))

(mapcar #'disable-theme custom-enabled-themes)

(mapcar (lambda (theme) (load-theme theme t)) current-themes)

result)))

(advice-add #'org-export-to-file :around (apply-partially #'my/with-theme 'solarized-dark))

(advice-add #'org-export-to-buffer :around (apply-partially #'my/with-theme 'solarized-dark))Voilà, no more bizarrely formatted code block exports from whatever theme I might have loaded at the time :)

Recursive HTTP Requests with Elm programming elm

CLOSED: [2018-01-22 Mon]

So I got the idea in my head that I wanted to pull data from the GitLab / GitHub APIs in my Elm app. This seemed straightforward enough; just wire up an HTTP request and a JSON decoder, and off I go. Then I remember, oh crap… like any sensible API with a potentially huge amount of data behind it, the results come back paginated. For anyone unfamiliar, this means that a single API request for a list of, say, repositories, is only going to return up to some maximum number of results. If there are more results available, there will be a reference to additional pages of results, that you can then fetch with another API request. My single request decoding only the results returned from that single request wasn't going to cut it.

I had a handful of problems to solve. I needed to:

- Detect when additional results were available.

- Parse out the URL to use to fetch the next page of results.

- Continue fetching results until none remained.

- Combine all of the results, maintaining their order.

Are there more results?

The first two bullet points can be dealt with by parsing and inspecting the response header. Both GitHub and GitLab embed pagination links in the HTTP Link header. As I'm interested in consuming pages until no further results remain, I'll be looking for a link in the header with the relationship "next". If I find one, I know I need to hit the associated URL to fetch more results. If I don't find one, I'm done!

Link: <https://api.github.com/user/repos?page=3&per_page=100>; rel="next",

<https://api.github.com/user/repos?page=50&per_page=100>; rel="last"Parsing this stuff out went straight into a utility module.

module Paginated.Util exposing (links)

import Dict exposing (Dict)

import Maybe.Extra

import Regex

{-| Parse an HTTP Link header into a dictionary. For example, to look

for a link to additional results in an API response, you could do the

following:

Dict.get "Link" response.headers

|> Maybe.map links

|> Maybe.andThen (Dict.get "next")

-}

links : String -> Dict String String

links s =

let

toTuples xs =

case xs of

[ Just a, Just b ] ->

Just ( b, a )

_ ->

Nothing

in

Regex.find

Regex.All

(Regex.regex "<(.*?)>; rel=\"(.*?)\"")

s

|> List.map .submatches

|> List.map toTuples

|> Maybe.Extra.values

|> Dict.fromList

A little bit of regular expression magic, tuples, and

Maybe.Extra.values to keep the matches, and now I've got my

(Maybe) URL.

Time to make some requests

Now's the time to define some types. I'll need a Request, which will

be similar to a standard Http.Request, with a slight difference.

type alias RequestOptions a =

{ method : String

, headers : List Http.Header

, url : String

, body : Http.Body

, decoder : Decoder a

, timeout : Maybe Time.Time

, withCredentials : Bool

}

type Request a

= Request (RequestOptions a)

What separates it from a basic Http.Request is the decoder field

instead of an expect field. The expect field in an HTTP request is

responsible for parsing the full response into whatever result the

caller wants. For my purposes, I always intend to be hitting a JSON

API returning a list of items, and I have my own designs on parsing

bits of the request to pluck out the headers. Therefore, I expose only

a slot for including a JSON decoder representing the type of item I'll

be getting a collection of.

I'll also need a Response, which will either be Partial

(containing the results from the response, plus a Request for

getting the next batch), or Complete.

type Response a

= Partial (Request a) (List a)

| Complete (List a)

Sending the request isn't too bad. I can just convert my request into

an Http.Request, and use Http.send.

send :

(Result Http.Error (Response a) -> msg)

-> Request a

-> Cmd msg

send resultToMessage request =

Http.send resultToMessage <|

httpRequest request

httpRequest : Request a -> Http.Request (Response a)

httpRequest (Request options) =

Http.request

{ method = options.method

, headers = options.headers

, url = options.url

, body = options.body

, expect = expect options

, timeout = options.timeout

, withCredentials = options.withCredentials

}

expect : RequestOptions a -> Http.Expect (Response a)

expect options =

Http.expectStringResponse (fromResponse options)

All of my special logic for handling the headers, mapping the decoder

over the results, and packing them up into a Response is baked into

my Http.Request via a private fromResponse translator:

fromResponse :

RequestOptions a

-> Http.Response String

-> Result String (Response a)

fromResponse options response =

let

items : Result String (List a)

items =

Json.Decode.decodeString

(Json.Decode.list options.decoder)

response.body

nextPage =

Dict.get "Link" response.headers

|> Maybe.map Paginated.Util.links

|> Maybe.andThen (Dict.get "next")

in

case nextPage of

Nothing ->

Result.map Complete items

Just url ->

Result.map

(Partial (request { options | url = url }))

itemsPutting it together

Now, I can make my API request, and get back a response with

potentially partial results. All that needs to be done now is to make

my request, and iterate on the results I get back in my update

method.

To make things a bit easier, I add a method for concatenating two responses:

update : Response a -> Response a -> Response a

update old new =

case ( old, new ) of

( Complete items, _ ) ->

Complete items

( Partial _ oldItems, Complete newItems ) ->

Complete (oldItems ++ newItems)

( Partial _ oldItems, Partial request newItems ) ->

Partial request (oldItems ++ newItems)Putting it all together, I get a fully functional test app that fetches a paginated list of repositories from GitLab, and renders them when I've fetched them all:

module Example exposing (..)

import Html exposing (Html)

import Http

import Json.Decode exposing (field, string)

import Paginated exposing (Response(..))

type alias Model =

{ repositories : Maybe (Response String) }

type Msg

= GotRepositories (Result Http.Error (Paginated.Response String))

main : Program Never Model Msg

main =

Html.program

{ init = init

, update = update

, view = view

, subscriptions = \_ -> Sub.none

}

init : ( Model, Cmd Msg )

init =

( { repositories = Nothing }

, getRepositories

)

update : Msg -> Model -> ( Model, Cmd Msg )

update msg model =

case msg of

GotRepositories (Ok response) ->

( { model

| repositories =

case model.repositories of

Nothing ->

Just response

Just previous ->

Just (Paginated.update previous response)

}

, case response of

Partial request _ ->

Paginated.send GotRepositories request

Complete _ ->

Cmd.none

)

GotRepositories (Err _) ->

( { model | repositories = Nothing }

, Cmd.none

)

view : Model -> Html Msg

view model =

case model.repositories of

Nothing ->

Html.div [] [ Html.text "Loading" ]

Just (Partial _ _) ->

Html.div [] [ Html.text "Loading..." ]

Just (Complete repos) ->

Html.ul [] <|

List.map

(\x -> Html.li [] [ Html.text x ])

repos

getRepositories : Cmd Msg

getRepositories =

Paginated.send GotRepositories <|

Paginated.get

"http://git.phoenixinquis.net/api/v4/projects?per_page=5"

(field "name" string)There's got to be a better way

I've got it working, and it's working well. However, it's kind of a

pain to use. It's nice that I can play with the results as they come

in by peeking into the Partial structure, but it's a real chore to

have to stitch the results together in my application's update

method. It'd be nice if I could somehow encapsulate that behavior in

my request and not have to worry about the pagination at all in my

app.

It just so happens that, with Tasks, I can.

Feel free to check out the full library documentation and code referenced in this post here.

Continue on with part two, Cleaner Recursive HTTP Requests with Elm Tasks.

Cleaner Recursive HTTP Requests with Elm Tasks programming elm

CLOSED: [2018-01-23 Tue]

Continued from part one, Recursive HTTP Requests with Elm.

In my last post, I described my first pass at building a library to fetch data from a paginated JSON REST API. It worked, but it wasn't too clean. In particular, the handling of the multiple pages and concatenation of results was left up to the calling code. Ideally, both of these concerns should be handled by the library, letting the application focus on working with a full result set. Using Elm's Tasks, we can achieve exactly that!

What's a Task?

A Task is a data structure in Elm which represents an asynchronous

operation that may fail, which can be mapped and chained. What this

means is, we can create an action, transform it, and chain it with

additional actions, building up a complex series of things to do into

a single Task, which we can then package up into a Cmd and hand to

the Elm runtime to perform. You can think of it like building up a

Future or Promise, setting up a sort of callback chain of mutations

and follow-up actions to be taken. The Elm runtime will work its way

through the chain and hand your application back the result in the

form of a Msg.

So, tasks sound great!

Moving to Tasks

Just to get things rolling, let's quit using Http.send, and instead

prepare a simple toTask function leveraging the very handy

Http.toTask. This'll give us a place to start building up some more

complex behavior.

send :

(Result Http.Error (Response a) -> msg)

-> Request a

-> Cmd msg

send resultToMessage request =

toTask request

|> Task.attempt resultToMessage

toTask : Request a -> Task Http.Error (Response a)

toTask =

httpRequest >> Http.toTaskShifting the recursion

Now, for the fun bit. We want, when a request completes, to inspect

the result. If the task failed, we do nothing. If it succeeded, we

move on to checking the response. If we have a Complete response,

we're done. If we do not, we want to build another task for the next

request, and start a new iteration on that.

All that needs to be done here is to chain our response handling using

Task.andThen, and either recurse to continue the chain with the next

Task, or wrap up the final results with Task.succeed!

recurse :

Task Http.Error (Response a)

-> Task Http.Error (Response a)

recurse =

Task.andThen

(\response ->

case response of

Partial request _ ->

httpRequest request

|> Http.toTask

|> recurse

Complete _ ->

Task.succeed response

)

That wasn't so bad. The function recursion almost seems like cheating:

I'm able to build up a whole chain of requests based on the results

without actually having the results yet! The Task lets us define a

complete plan for what to do with the results, using what we know

about the data structures flowing through to make decisions and tack

on additional things to do.

Accumulating results

There's just one thing left to do: we're not accumulating results yet. We're just handing off the results of the final request, which isn't too helpful to the caller. We're also still returning our Response structure, which is no longer necessary, since we're not bothering with returning incomplete requests anymore.

Cleaning up the types is pretty easy. It's just a matter of switching

out some instances of Response a with List a in our type

declarations…

send :

(Result Http.Error (List a) -> msg)

-> Request a

-> Cmd msg

toTask : Request a -> Task Http.Error (List a)

recurse :

Task Http.Error (Response a)

-> Task Http.Error (List a)

…then changing our Complete case to return the actual items:

Complete xs ->

Task.succeed xs

The final step, then, is to accumulate the results. Turns out this is

super easy. We already have an update function that combines two

responses, so we can map that over our next request task so that it

incorporates the previous request's results!

Partial request _ ->

httpRequest request

|> Http.toTask

|> Task.map (update response)

|> recurseTidying up

Things are tied up pretty neatly, now! Calling code no longer needs to

care whether the JSON endpoints its calling paginate their results,

they'll receive everything they asked for as though it were a single

request. Implementation details like the Response structure,

update method, and httpRequest no longer need to be exposed.

toTask can be exposed now as a convenience to anyone who wants to

perform further chaining on their calls.

Now that there's a cleaner interface to the module, the example app is looking a lot cleaner now, too:

module Example exposing (..)

import Html exposing (Html)

import Http

import Json.Decode exposing (field, string)

import Paginated

type alias Model =

{ repositories : Maybe (List String) }

type Msg

= GotRepositories (Result Http.Error (List String))

main : Program Never Model Msg

main =

Html.program

{ init = init

, update = update

, view = view

, subscriptions = \_ -> Sub.none

}

init : ( Model, Cmd Msg )

init =

( { repositories = Nothing }

, getRepositories

)

update : Msg -> Model -> ( Model, Cmd Msg )

update msg model =

case msg of

GotRepositories result ->

( { model | repositories = Result.toMaybe result }

, Cmd.none

)

view : Model -> Html Msg

view model =

case model.repositories of

Nothing ->

Html.div [] [ Html.text "Loading" ]

Just repos ->

Html.ul [] <|

List.map

(\x -> Html.li [] [ Html.text x ])

repos

getRepositories : Cmd Msg

getRepositories =

Paginated.send GotRepositories <|

Paginated.get

"http://git.phoenixinquis.net/api/v4/projects?per_page=5"

(field "name" string)

So, there we have it! Feel free to check out the my complete

Paginated library on the Elm package index, or on GitHub. Hopefully

you'll find it or this post useful. I'm still finding my way around

Elm, so any and all feedback is quite welcome :)

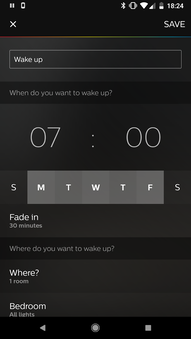

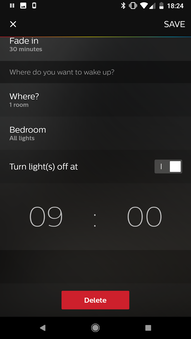

How Does The Phillips Hue Wake-Up Feature Work? home_automation

CLOSED: [2018-03-13 Tue]

I recently got myself a set of Phillips Hue White and Color Ambiance lights. One of the features I was looking forward to in particular (besides playing with all the color options) was setting a wake-up alarm with the lights gradually brightening. This was pretty painless to get set up using the phone app. I'm pretty happy with the result, but there's certainly some things I wouldn't mind tweaking. For example, the initial brightness of the bulbs (at the lowest setting) still seems a bit bright, so I might want to delay the bedside lamps and let the more distant lamp start fading in first. I also want to see if I can fiddle it into transitioning between some colors to get more of a sunrise effect (perhaps "rising" from the other side of the room, with the light spreading towards the head of the bed).

Figuring out how the wake-up settings that the app installed on my bridge seemed a good first step towards introducing my own customizations.

Information on getting access to a Hue bridge to make REST API calls to it can be found in the Hue API getting started guide.

My wake-up settings

My wake-up is scheduled for 7:00 to gradually brighten the lights with a half-hour fade-in each weekday. I also toggled on the setting to automatically turn the lights off at 9:00.

Finding things on the bridge

The most natural starting point is to check the schedules. Right off the bat, I find what I'm after:

The schedule …

GET http://bridge/api/${username}/schedules/1{

"name": "Wake up",

"description": "L_04_fidlv_start wake up",

"command": {

"address": "/api/xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx/sensors/2/state",

"body": {

"flag": true

},

"method": "PUT"

},

"localtime": "W124/T06:30:00",

"time": "W124/T10:30:00",

"created": "2018-03-11T19:46:54",

"status": "enabled",

"recycle": true

}

This is a recurring schedule item that runs every weekday at 6:30. We

can tell this by looking at the localtime field. From the

documentation on time patterns, we can see that it's a recurring time

pattern specifying days of the week as a bitmask, and a time (6:30).

0MTWTFSS |

01111100 (124 in decimal) |

Since this schedule is enabled, we can be assured that it will run,

and in doing so, will issue a PUT to a sensors endpoint, setting a

flag to true.

… triggers the sensor …

GET http://bridge/api/${username}/sensors/2{

"state": {

"flag": false,

"lastupdated": "2018-03-13T13:00:00"

},

"config": {

"on": true,

"reachable": true

},

"name": "Sensor for wakeup",

"type": "CLIPGenericFlag",

"modelid": "WAKEUP",

"manufacturername": "xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx",

"swversion": "A_1801260942",

"uniqueid": "L_04_fidlv",

"recycle": true

}The sensor is what's really setting things in motion. Here we've got a generic CLIP flag sensor that is triggered exclusively by our schedule. Essentially, by updating the flag state, we trigger the sensor.

… triggers a rule …

GET http://bridge/api/${username}/rules/1{

"name": "L_04_fidlv_Start",

"owner": "xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx",

"created": "2018-03-11T19:46:51",

"lasttriggered": "2018-03-13T10:30:00",

"timestriggered": 2,

"status": "enabled",

"recycle": true,

"conditions": [

{

"address": "/sensors/2/state/flag",

"operator": "eq",

"value": "true"

}

],

"actions": [

{

"address": "/groups/1/action",

"method": "PUT",

"body": {

"scene": "7GJer2-5ahGIqz6"

}

},

{

"address": "/schedules/2",

"method": "PUT",

"body": {

"status": "enabled"

}

}

]

}

Now things are happening. Looking at the conditions, we can see that

this rule triggers when the wakeup sensor updates, and its flag is set

to true. When that happens, the bridge will iterate through its

rules, find that the above condition has been met, and iterate through

each of the actions.

… which sets the scene …

The bedroom group (/groups/1 in the rule's action list) is set to

the following scene, which turns on the lights at minimum brightness:

GET http://bridge/api/${username}/scenes/7GJer2-5ahGIqz6{

"name": "Wake Up init",

"lights": [

"2",

"3",

"5"

],

"owner": "xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx",

"recycle": true,

"locked": true,

"appdata": {},

"picture": "",

"lastupdated": "2018-03-11T19:46:50",

"version": 2,

"lightstates": {

"2": {

"on": true,

"bri": 1,

"ct": 447

},

"3": {

"on": true,

"bri": 1,

"ct": 447

},

"5": {

"on": true,

"bri": 1,

"ct": 447

}

}

}… and schedules the transition …

Another schedule (/schedules/2 in the rule's action list) is enabled

by the rule.

GET http://bridge/api/${username}/schedules/2{

"name": "L_04_fidlv",

"description": "L_04_fidlv_trigger end scene",

"command": {

"address": "/api/xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx/groups/0/action",

"body": {

"scene": "gXdkB1um68N1sZL"

},

"method": "PUT"

},

"localtime": "PT00:01:00",

"time": "PT00:01:00",

"created": "2018-03-11T19:46:51",

"status": "disabled",

"autodelete": false,

"starttime": "2018-03-13T10:30:00",

"recycle": true

}

This schedule is a bit different from the one we saw before. It is

normally disabled, and it's time pattern (in localtime) is

different. The PT prefix specifies that this is a timer which

expires after the given amount of time has passed. In this case, it is

set to one minute (the first 60 seconds of our wake-up will be spent

in minimal lighting). Enabling this schedule starts up the timer. When

one minute is up, another scene will be set.

This one, strangely, is applied to group 0, the meta-group including

all lights, but since the scene itself specifies to which lights it

applies, there's no real problem with it.

… to a fully lit room …

GET http://bridge/api/${username}/scenes/gXdkB1um68N1sZL{

"name": "Wake Up end",

"lights": [

"2",

"3",

"5"

],

"owner": "xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx",

"recycle": true,

"locked": true,

"appdata": {},

"picture": "",

"lastupdated": "2018-03-11T19:46:51",

"version": 2,

"lightstates": {

"2": {

"on": true,

"bri": 254,

"ct": 447,

"transitiontime": 17400

},

"3": {

"on": true,

"bri": 254,

"ct": 447,

"transitiontime": 17400

},

"5": {

"on": true,

"bri": 254,

"ct": 447,

"transitiontime": 17400

}

}

}

This scene transitions the lights to full brightness over the next 29

minutes (1740 seconds), per the specified transitiontime (which is

specified in deciseconds).

… which will be switched off later.

Finally, an additional rule takes care of turning the lights off and the wake-up sensor at 9:00 (Two and a half hours after the initial triggering of the sensor).

GET http://bridge/api/${username}/rules/2{

"name": "Wake up 1.end",

"owner": "xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx",

"created": "2018-03-11T19:46:51",

"lasttriggered": "2018-03-13T13:00:00",

"timestriggered": 2,

"status": "enabled",

"recycle": true,

"conditions": [

{

"address": "/sensors/2/state/flag",

"operator": "eq",

"value": "true"

},

{

"address": "/sensors/2/state/flag",

"operator": "ddx",

"value": "PT02:30:00"

}

],

"actions": [

{

"address": "/groups/2/action",

"method": "PUT",

"body": {

"on": false

}

},

{

"address": "/sensors/2/state",

"method": "PUT",

"body": {

"flag": false

}

}

]

}

Unlike the first rule, this one doesn't trigger immediately. It has an

additional condition on the sensor state flag using the special ddx

operator, which (given the timer specified) is true two and a half

hours after the flag has been set. As the schedule sets it at 6:30,

that means that this rule will trigger at 9:00, turn the lights off in

the bedroom, and set the sensor's flag to false.

Where to go from here

The wake-up config in the phone app touched on pretty much every major aspect of the Hue bridge API. Given the insight I now have into how it works, I can start constructing my own schedules and transitions, and playing with different ways of triggering them and even having them trigger each other.

If I get around to building my rolling sunrise, I'll be sure to get a post up on it :)